The Role of Luck in Life is Still Misunderstood

15 Mar 2018The paper Talent vs Luck: the role of randomness in success and failure, by A. Pluchino. A. E. Biondo, and A. Rapisarda, has been receiving a lot of positive reception lately.

Unfortunately, the public response has been far too weak in questioning this paper’s claims. The results of its model are discussed in persuasive but misleading ways. The authors do not sufficiently justify the model’s design and validity. Its results feel more a consequence of its design than a proof that similar factors govern career success. Overall this leaves the model feeling contrived, and a poor base from which to extract learnings on real world dynamics.

To be clear, I care deeply about the issue of growing wealth inequality, and would love for research to be done that finds concrete evidence of how luck and privilege play a role in it. I’m all for finding ways we can adapt policy to help correct for non-meritocratic dynamics.

But it’s important that we make sure public policy (and opinion) shifts on the basis of good, unbiased, verified, repeatable insights coming from the research done on these topics.

In the paper, there’s a big gap between its wide-sweeping claims and the validity of the underlying model. Charts and numbers give the illusion of convincing support which, added together with its alignment to popular world views, make the paper quite persuasive. This has led to impressive headlines that herald the paper as if it’s concrete proof, like “The Role of Luck in Life Success Is Far Greater Than We Realized”, or “If you’re so smart, why aren’t you rich? Turns out it’s just chance.”.

This coverage is coming from reputed sources: these last two headlines are from Scientific American and the MIT Review. There’s a serious risk of this runaway momentum building an ever-growing chain of misguided agreement.

This fanfare is seriously misplaced. Let’s get into why.

I. Model Basics

The paper proposes an agent-based model to simulate the role of talent and luck in career success. This way of modeling involves placing agents, representing people, onto a 2D space and observing how they interact with their environment over time. Running into lucky and unlucky events, which move randomly through the environment, provide people chances at gaining or losing capital.

Initially, 1000 people are given an equal amount of capital (10 units), and a normal distribution of talent (ranging from 0 - 1.0, with a mean of 0.6). When they encounter a lucky event, a random number is generated between 0 and 1. If the agent’s talent rating exceeds this number, their capital is immediately doubled. In encounters with unlucky events, an agent’s capital is halved, regardless of talent.

Over the course of 40 years, or 80 steps representing 6 months each, capital distribution changes. In the paper’s results, the authors note that 20% of the population control 80% of the wealth. A select few individuals have an exorbitant amount of capital. This is similar to widely accepted views on the world’s current distribution of wealth.

II. Misleading and overreaching results

I feel the paper’s findings are formed in misleading ways, by using data that don’t actually support neighbouring arguments and by omitting key elements. The authors note that the highest-wealth agents in their model primarily come from nearer-to-average talent levels, leading them to state that “less talented people are very often able to reach the top”. They underscore that, in 100 runs of the model, agents with exceptionally high talent win the most capital just 3% of the time, building a narrative that these outcomes are perverse or objectionable.

But these data points are statistically misleading. No reference is made to the relative size of the talent brackets, a convenient omission when we’re being told about less talented success occurring “very often”. The exceptionally high talented group is, by definition, a set of about 2% or 20-odd people, which means winning 3% of the time may not actually be a poor rate of success. Meanwhile, the nearer-to-average brackets have the largest populations. They aren’t necessarily winning “very often” - they just have more people to start out.

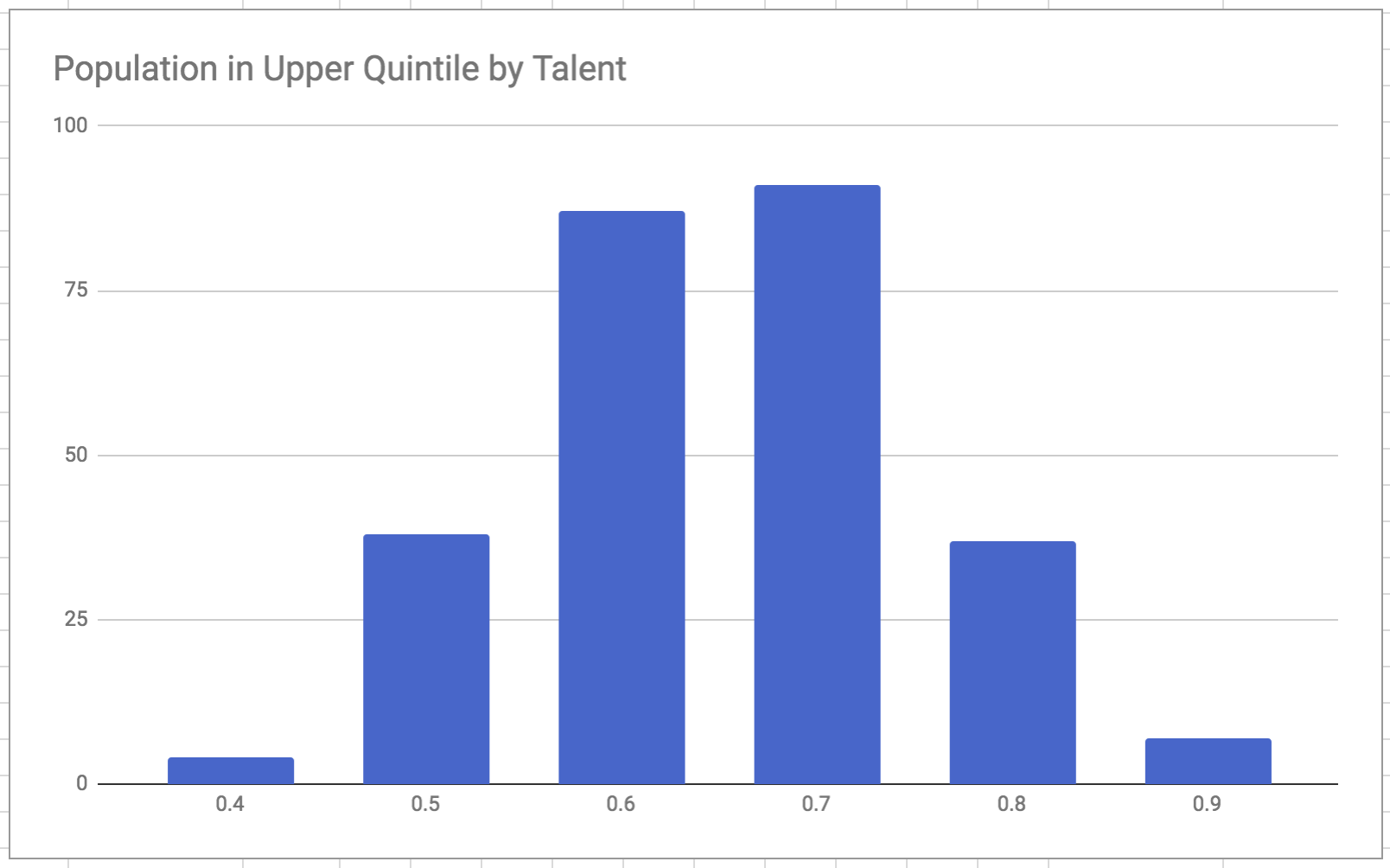

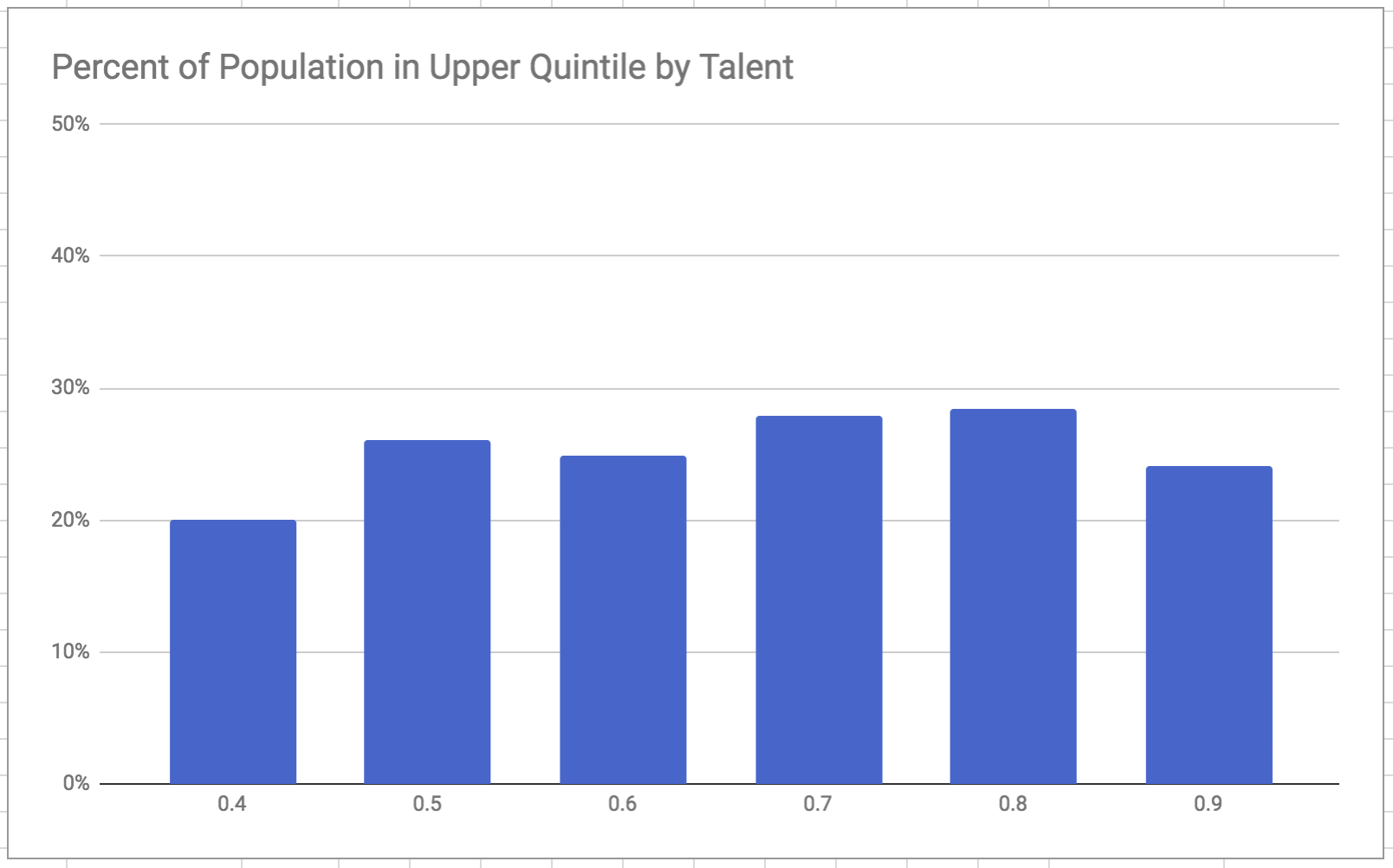

To make this less theoretical, consider the two charts below, which display results from a run using my own recreation of the model. The first chart shows the absolute number of people from each bracket making it to the wealthiest quintile. We see a similar trend here as in the paper, where the top quintile is dominated by people of nearer-to-average talent. The second chart shows the proportion of people in each bracket making to the top quintile.

This lower chart pokes a major hole in the narrative the authors build up to. There isn’t a clear message that the nearer-to-average brackets succeed “very often” compared to the others - certainly not in an extreme or perverse way. It is curious that this view of the data was left out.

III. Could it still be luck?

That said, the lower chart indeed indicates that luck is playing an outsize role in capital outcomes. Though the lowest bracket succeeds slightly less often, there isn’t a significant trend of greater success with higher talent. Surely this means the model still shows our career success is not meritocratic, right?

Wrong - the model and its variations do not provide a base for gleaning wider learnings unless they actually simulate the real world. Without establishing that, the model and its modifications are just fictional simulations, not an exercise we can use to learn more about career success, inequality, or otherwise.

IV. Model (In)Validity

In searching through the paper for sections establishing how the model validly simulates career success, the most I could find were notes that its results exhibited similar features as real world wealth inequality. The authors state that the model follows the 80/20 rule, and that its results fit well with the power law.

The results-looks-similar argument is hardly a convincing one. It could be that the results were built into the model’s design. Indeed, based on the way its rules are set, the high concentrations of capital seem like they were a foregone conclusion.

The rules governing capital growth mean it will roughly grow by the exponent of the number of lucky events an agent comes across, and fall with unlucky ones. Like getting an improbable series of heads when flipping a coin long enough, improbable clusters of events are bound to occur for at least some agents in a large enough set. With an exponential growth function at work, it’s no wonder that we see high concentrations of capital come out.

This might be fine if the core rules of the model bore self-evident ties back to career dynamics and earnings, but they don’t. Why should capital growth only occur on chance events, when most workers are paid wages in exchange for their work? Why is its growth defined as exponential? If the model were being used to look at investment outcomes or financial trading, these rules would perhaps seem more self-evident.

But the model is being used to draw conclusions on career success, funding and educational policies. Though there is some mention of prior research on how luck plays a large role in people’s lives, I can find no section in the paper discussing the design of the model’s rules as it relates back to the areas its insights are supposed to apply to.

V. We can do better

For me, the paper falls flat compared to its claims. There is a lack of convincing discussion on the model’s ties to the real world, and data is used & omitted in convenient if not spurious ways. It feels more like the authors had a set of conclusions they built a corresponding model for than that they aimed to build a model for career success and explore its results in an open ended fashion.

If the aim is to mitigate contributing factors to wealth inequality, changes need to be based on solid research. Models must be shown to have been designed to explore the issues, not risk appearing to be designed to obtain specific results. Most importantly, conclusions need to be drawn from unbiased explorations of the data, not the other way around.

This paper comes up short on these fronts. This is disappointing because I really do think that factors like luck & privilege play a role in wealth inequality, and that certain policies can compound or mitigate these unequal outcomes.

That said, I would be glad to see my points above countered, should the authors provide information helping to address these concerns, and hope to see more research on this topic in the future.

Notes & Acknowledgements

Special thanks to my brother, Gid, for his help discussing the paper & reviewing this post.

Here is a spreadsheet with the raw data and analysis of from the run referenced above.